The Lenten message of Emmanuel practitioners that influenced the occupational therapy profession

I have previously documented (in presentation and in blog) the role of the Emmanuel Movement with regard to its overall impact on 'treatment' of mental health conditions at the turn of the century in general and its impact on George Barton in particular. I have also documented some lingering impact of concerns with spirituality and how the topic has been reflected in some occupational therapy documents over time. As we are on the eve of the Lenten season, and as we are properly situated in history to reflect on the crucible of values that contributed to the founding of the occupational therapy profession, this little sideways journey seems timely and appropriate.

Many occupational therapists enjoy using the term 'holistic' to describe their orientation and interest but few are adroitly capable of putting such diversity that includes spirituality into actual practice. This has always been the case - even when turn of the 20th century 'providers' made the attempt.

Emmanuel methods centered around a merger between medicine and spirituality: a medical clinic with free weekly examinations, a weekly health class with multidisciplinary lectures on medical, psychological and spiritual health, and private psychotherapy/counseling sessions. Reverend Elwood Worcester, founder of this movement, specifically recruited well known Boston physicians (Putnam, Cabot, Pratt, and Coriat) to lend medical credibility to his ministerial efforts (Caplan, 1998).

From the start, Elwood Worcester had difficulty distancing his methods from the controversial Christian Science movement and the work of Mary Baker Eddy. The methods were not at all similar; in fact Eddy spoke out against what some termed the 'mind cure movement' and specifically stated her opposition to people like Worcester. These differences were outlined extensively in Willa Cather's series that appeared in McClure magazine from January 1907-June 1908 (nom de plume Georgine Milmine).

Clarence Farrar was a prominent psychiatrist who leveled blistering attacks on the Emmanuelists (1909), stating that their "faddist faith cure movement" arose from Boston, "the land of witchcraft and transcendentalism." This kind of criticism from prominent medical leaders led to the waning of support from the Boston doctors that Worcester recruited. As explained by Caplan (1998), these criticisms may have been primarily motivated by a desire for 'control' over the growing psychological movement. Worcester and his colleague Samuel McComb attempted to respond (1909) but at that point the opinions of most medical practitioners were settled: psychotherapeutics was to be the domain of doctors and not of the clergy.

The criticism was so powerful and effective that concerns were echoed many years later by occupational therapy leaders. In the Fifth Annual Meeting of the American Occupational Therapy Association there was discussion about the need to develop a research base to help doctors understand the role of the new profession. Herbert Hall (1922) stated, "We must be careful not to go about making claims for occupational therapy as the Christian Scientists do for their methods." The Emmanuel practitioners were never able to fully shake the incorrect association of their approach with the Eddyists, and it is clear that physicians like Hall were sensitive to the negative association.

One of the final formal defenses of the Emmanuel method was published as an article in Good Housekeeping entitled Lent: A friend to the nervous (McComb, 1910). Given the current season I choose to highlight this article in particular.

The article is interesting not only for its chronology in the medicine vs. religion debate, but also for its clarity in describing the universality of a 'Lenten' experience. McComb wrote

McComb further argued that Wordsworth (notably, a Transcendentalist) was sadly correct:

McComb believed that the Lenten season, applied across religious or non-religious convictions, could serve as a model for taking a pause in the busy-ness of life that was so culturally and socially unsettled at the time. This is the precise message that was given to George Barton by Worcester - a directive to let go of his own suffering and to make sacrifices for 'the other fellow.'

The Lenten season, from religious definition, is all about hope and an Easter beginning. The Lenten 'experience,' from a secular perspective, is an application of spiritual hope on a backdrop of confused and complicated modern living.

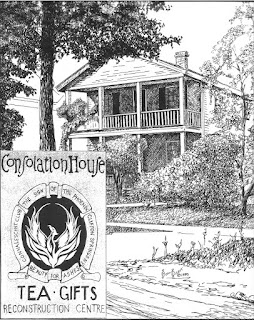

As a Christian man, Barton interpreted the Emmanuel Church message in directly Biblical terms, specifically related to Isaiah 61:3 when he used the term 'Beauty for Ashes' on his Consolation House logo (see picture above). However, the Emmanuel Movement's message was more broad than simple and direct religious application, as summarized by McComb:

That was McComb's Lenten message, and it was the basis for an occupational therapy message that Barton put into action at his Consolation House project.

References

embedded links, and...

Archives of Occupational Therapy (1922). The Fifth Annual Meeting of the American Occupational Therapy Association, Meeting of the Board and Members of the House of Delegates.

Caplan, Eric (1998). Mind Games: American Culture and the Birth of Psychotherapy. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press. Chapter 6: Embracing psychotherapy: The Emmanuel Movement and the American Medical Profession. Available online at http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft7g5007w4&chunk.id=d0e3438&toc.depth=1&toc.id=d0e3438&brand=ucpress

Farrar, C.B. (1909). Psychotherapy and the Church, Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 36, 11-24

McComb, S. (1910). Lent: A friend to the nervous. Good Housekeeping, 50(3), 327-329.

Worcester, E. & McComb, S. (1909). Christian Religion as a Healing Power. New York: Moffat, Yard.

Many occupational therapists enjoy using the term 'holistic' to describe their orientation and interest but few are adroitly capable of putting such diversity that includes spirituality into actual practice. This has always been the case - even when turn of the 20th century 'providers' made the attempt.

Emmanuel methods centered around a merger between medicine and spirituality: a medical clinic with free weekly examinations, a weekly health class with multidisciplinary lectures on medical, psychological and spiritual health, and private psychotherapy/counseling sessions. Reverend Elwood Worcester, founder of this movement, specifically recruited well known Boston physicians (Putnam, Cabot, Pratt, and Coriat) to lend medical credibility to his ministerial efforts (Caplan, 1998).

From the start, Elwood Worcester had difficulty distancing his methods from the controversial Christian Science movement and the work of Mary Baker Eddy. The methods were not at all similar; in fact Eddy spoke out against what some termed the 'mind cure movement' and specifically stated her opposition to people like Worcester. These differences were outlined extensively in Willa Cather's series that appeared in McClure magazine from January 1907-June 1908 (nom de plume Georgine Milmine).

Clarence Farrar was a prominent psychiatrist who leveled blistering attacks on the Emmanuelists (1909), stating that their "faddist faith cure movement" arose from Boston, "the land of witchcraft and transcendentalism." This kind of criticism from prominent medical leaders led to the waning of support from the Boston doctors that Worcester recruited. As explained by Caplan (1998), these criticisms may have been primarily motivated by a desire for 'control' over the growing psychological movement. Worcester and his colleague Samuel McComb attempted to respond (1909) but at that point the opinions of most medical practitioners were settled: psychotherapeutics was to be the domain of doctors and not of the clergy.

The criticism was so powerful and effective that concerns were echoed many years later by occupational therapy leaders. In the Fifth Annual Meeting of the American Occupational Therapy Association there was discussion about the need to develop a research base to help doctors understand the role of the new profession. Herbert Hall (1922) stated, "We must be careful not to go about making claims for occupational therapy as the Christian Scientists do for their methods." The Emmanuel practitioners were never able to fully shake the incorrect association of their approach with the Eddyists, and it is clear that physicians like Hall were sensitive to the negative association.

One of the final formal defenses of the Emmanuel method was published as an article in Good Housekeeping entitled Lent: A friend to the nervous (McComb, 1910). Given the current season I choose to highlight this article in particular.

The article is interesting not only for its chronology in the medicine vs. religion debate, but also for its clarity in describing the universality of a 'Lenten' experience. McComb wrote

Now I would like to contradict this idea [Lent as an ecclesiastical custom] and to assert very emphatically that while Lent may and ought to be used for ends that are strictly religious, it is pre-eminently a human institution, with a vital bearing on our earthly life and happiness. We all need, at times, a complete break with our accustomed habits, with our ordinary ways of thinking, with our usual food and drink and recreations; and we all need this because we are all accustomed to get into ruts and grooves, until we become, as it were, mental and physical automatons instead of living, progressing, moral beings.

McComb further argued that Wordsworth (notably, a Transcendentalist) was sadly correct:

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;-

Little we see in Nature that is ours

McComb believed that the Lenten season, applied across religious or non-religious convictions, could serve as a model for taking a pause in the busy-ness of life that was so culturally and socially unsettled at the time. This is the precise message that was given to George Barton by Worcester - a directive to let go of his own suffering and to make sacrifices for 'the other fellow.'

The Lenten season, from religious definition, is all about hope and an Easter beginning. The Lenten 'experience,' from a secular perspective, is an application of spiritual hope on a backdrop of confused and complicated modern living.

As a Christian man, Barton interpreted the Emmanuel Church message in directly Biblical terms, specifically related to Isaiah 61:3 when he used the term 'Beauty for Ashes' on his Consolation House logo (see picture above). However, the Emmanuel Movement's message was more broad than simple and direct religious application, as summarized by McComb:

Lent is a reminder that two worlds are ours: the lower, with its miseries, its cares, its distractions, its worries; and the higher world within to which we can make our escape, with its faith and hope and love and peace. As we lay hold of this higher, the lower world loses its grip upon us, ceases to paralyze us; and while we may not claim any mere stagnation or brute freedom from toil and care and responsibility, we may, nevertheless, have a secret that makes music in the heart and nerves us to rise triumphant over the strains and stresses of experience.

That was McComb's Lenten message, and it was the basis for an occupational therapy message that Barton put into action at his Consolation House project.

References

embedded links, and...

Archives of Occupational Therapy (1922). The Fifth Annual Meeting of the American Occupational Therapy Association, Meeting of the Board and Members of the House of Delegates.

Caplan, Eric (1998). Mind Games: American Culture and the Birth of Psychotherapy. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press. Chapter 6: Embracing psychotherapy: The Emmanuel Movement and the American Medical Profession. Available online at http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft7g5007w4&chunk.id=d0e3438&toc.depth=1&toc.id=d0e3438&brand=ucpress

Farrar, C.B. (1909). Psychotherapy and the Church, Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 36, 11-24

McComb, S. (1910). Lent: A friend to the nervous. Good Housekeeping, 50(3), 327-329.

Worcester, E. & McComb, S. (1909). Christian Religion as a Healing Power. New York: Moffat, Yard.

Comments